Aug. 28, 2019 – CommunityImpact – The city of Austin is proposing new speed management solutions, such as speed cushions and speed limit changes, for more roadways throughout Austin. (Amy Denney/Community Impact Newspaper)

Aug. 28, 2019 – CommunityImpact – The city of Austin is proposing new speed management solutions, such as speed cushions and speed limit changes, for more roadways throughout Austin. (Amy Denney/Community Impact Newspaper)In an effort to reduce the number of traffic fatalities and make streets safer, the city of Austin is taking what was once a neighborhood-focused approach and applying it citywide.

From 2014-19, the Austin Transportation Department has been installing speed cushions and other devices in an effort to control speed on neighborhood and small collector streets. In Northwest Austin on Mesa Drive south of Spicewood Springs Road where the speed limit is 30 mph, speed cushions installed in 2017 have helped reduce the number of vehicles traveling over 35 mph from almost 2,600 to about 200, according to city data.

However, new analysis of traffic collisions shows focusing speed-management efforts, such as reducing speed limits, on major roadways could have a greater impact on reducing the number of traffic fatalities and serious injuries resulting from traffic collisions.

However, new analysis of traffic collisions shows focusing speed-management efforts, such as reducing speed limits, on major roadways could have a greater impact on reducing the number of traffic fatalities and serious injuries resulting from traffic collisions.

“It’s important to change [street]design, but just lowering speed limits systemwide does actually cause people to drive safer,” said Jay Blazek Crossley, executive director of Farm & City, an Austin-based think tank focused on urban planning and transportation.

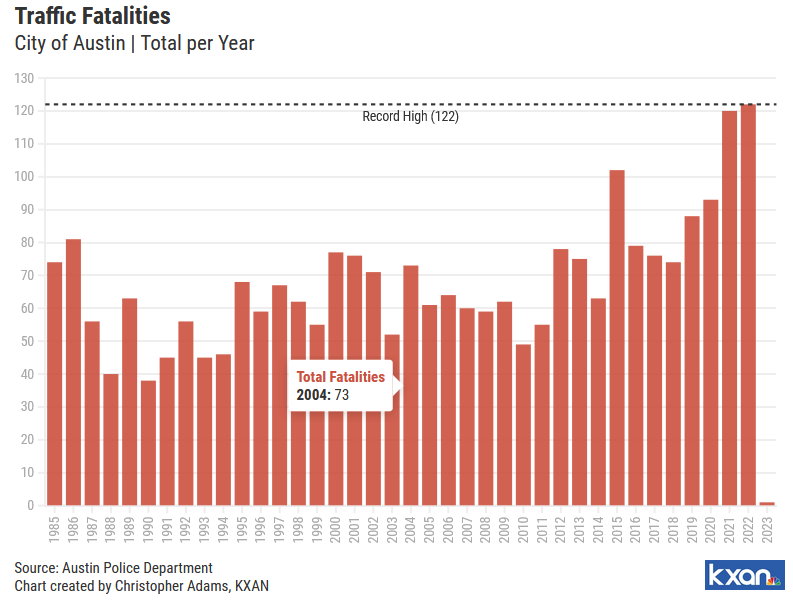

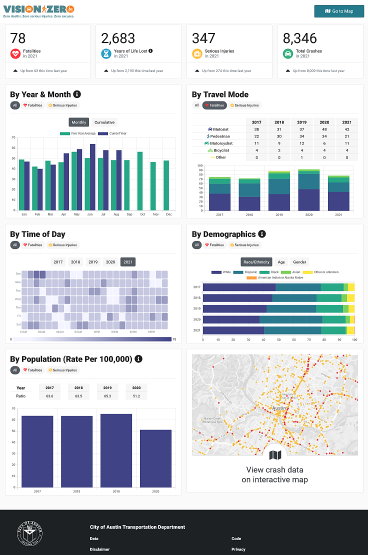

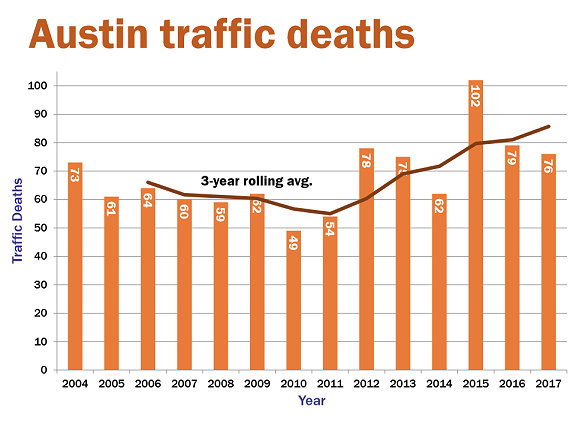

The city’s goal under its Vision Zero program is to have zero traffic fatalities by 2025. From 2012-18, the number of annual traffic fatalities has averaged 78, with a peak at 102 deaths in 2015, according to city data. About 68% of these fatalities occurred on 8% of the city’s streets, ATD Transportation Safety Officer Lewis Leff said. Targeting all streets under the speed management program could result in fewer traffic fatalities, he said.

“We need to do more—there’s fair criticism out there—and this [program]is one approach to a systemic change that we’d like to see help that goal,” Leff said.

Under the Local Area Traffic Management program, the city has spent $4.78 million since 2014 installing speed cushions, pedestrian islands, radar speed signs and other mitigation devices. The program was citizen-led in that residents submitted requests to the city for speed management devices, and the city conducted a speed study. Work remains on about a dozen projects that will be completed by January, including adding speed signs on Mesa.

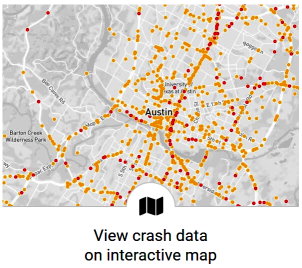

City data shows most traffic fatalities happen on larger roadways, such as Parmer Lane and Anderson Mill Road, so staffers created a high-injury network based on five years’ worth of data.

This map will help inform staffers where to spend an anticipated $500,000 on speed management in fiscal year 2019-20, said Eric Bollich, managing engineer for ATD’s Transportation Engineering Division. City Council is expected to adopt the budget in mid-September, and ATD is hoping to secure $141,147 to hire a program manager.

“We can focus on the high-injury network to really hone in on those hotspots,” he said. The transportation department also has an agreement with the Austin Police Department to target enforcement of speed limits on these high-injury roadways. “We’re seeing a lot of citations and warnings, and [the police are]getting out there to try to educate drivers at the same time about how important it is along those particular areas to pay attention to their speeds, reduce distracted driving, and yield to pedestrians and bicyclists and other vulnerable road users,” Leff said.

Crossley said he hopes the city continues to focus on neighborhood streets and not just high-injury roadways. “The safe neighborhood streets are very important, and every kid in Austin and corner of the region deserves the freedom to walk around in [their own]neighborhood,” he said.

In the Canyon Creek neighborhood of Northwest Austin, resident Katherine Cristobal has seen numerous collisions along Boulder Lane, the main roadway that connects to RM 620 and runs through the neighborhood. Speeding is a major concern, she said, adding a driver even ran through an iron fence near the day care center where her two children attend. “It’s very disturbing,” she said.

In the past year, the city added radar speed signs to tell drivers how fast they are going. But Cristobal said she wants to see lower speed limits on Boulder and even on RM 620.

“If they would lower the speed limit it might help because part of the reason people run so many red lights is they just don’t want to stop,” she said.

Lowering the speed limit on city- and state-owned roadways is another tool ATD is considering under its new speed-management program.

Leff said state code allows the city to conduct speed studies on a roadway to see if it would qualify for speed limit change. City Council could then change the speed limit by ordinance and determine the current speed to be unreasonable or unsafe. “We’re continuing to explore what that looks like,” Leff said.

Although the city has not yet named which streets it will consider for speed limit changes, Bollich said staffers analyzed the major corridors receiving funds from the 2016 Mobility Bond, which include Burnet Road and North Lamar Boulevard, as well as streets in the high-injury network.

Austin is one of three Texas cities that has adopted a Vision Zero goal and action plan aimed at eliminating traffic fatalities, Crossley said. The city’s Vision Zero plan revealed top intersections where traffic collisions occur, and the city improved five of the most dangerous intersections, which included Parmer and North Lamar as well as Rundberg Lane and Lamar. Safety improvements at those sites were completed in 2017. The new speed management program would aim to capitalize on these efforts and use other tools available to the city, such as adding rumble strips and installing speed signs.

Anderson Mill neighborhood resident Susan Reed said her neighborhood began a traffic initiative to reduce speeding near schools in Anderson Mill. Residents are working with Round Rock ISD, the PTAs, ATD, APD and Williamson County to create recommendations to reduce speeding and distracted driving near schools. She would also like to see more enforcement of speed limits in Anderson Mill. “A cooperative effort to solve a big problem like this is the only thing that works,” Reed said.

The Texas Department of Transportation is also focusing more on roadway safety. The state leads the nation in the number of traffic fatalities, according to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. In 2018, TxDOT reported 3,640 people died on Texas roads, a decrease from 3,727 deaths in 2017.

“Texas spends more money than any other state on roads. It’s not a question of spending more money, but use data and analysis to better spend money and fix things,” Crossley said.

The Texas Transportation Commission—TxDOT’s governing board—adopted in May a goal to cut in half the number of traffic fatalities by 2035 and reduce it to zero by 2050. At the July commission meeting, TxDOT announced a spending plan of $600 million over the next two years to put toward safety. The commission was scheduled to approve the amount at its Aug. 29 meeting.